Austronesian Origins

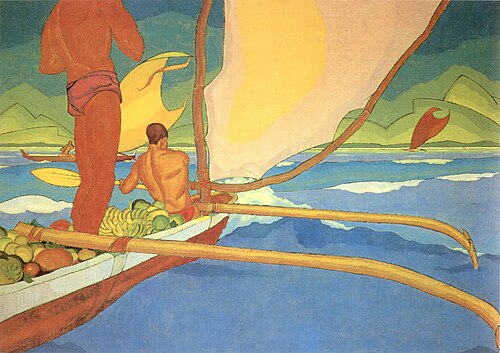

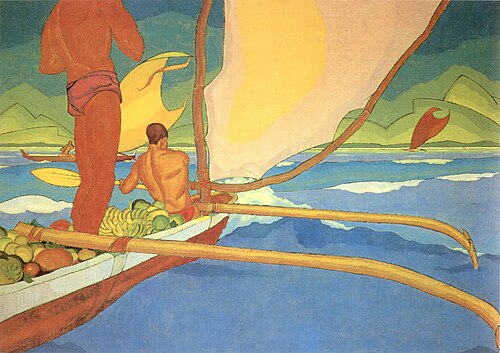

Factual information about the peopling of Madagascar remains incomplete, but much recent multidisciplinary research and work in archaeology, genetics, linguistics, and history confirms that the Malagasy people were originally and overwhelmingly Austronesian peoples native to the Sunda Islands. They probably arrived on the west coast of Madagascar with outrigger canoes (waka) at the beginning of our era or as much as 300 years sooner according to archaeologists, and perhaps even earlier under certain geneticists' assumptions. On the basis of plant cultigens, Blench proposed the migrations occurred "at the earliest century BCE". Archaeological work of Ardika and Bellwood suggests migration between 500 and 200 BCE.

The Borobudur Ship Expedition in 2003–2004 affirmed scholars' ideas that ships from ancient Indonesia could have reached Madagascar and the west African coast for trade from the 8th century and after. A traditional Borobudur ship with outriggers was reconstructed and sailed in this expedition from Jakarta to Madagascar and Ghana. As for the ancient route, one possibility is that Indonesian Austronesians came directly across the Indian Ocean from Java to Madagascar.

It is likely that they went through the Maldives where evidence of old Indonesian boat design and fishing technology persists until the present. The Malagasy language originated from the Southeast Barito language, and Ma'anyan language is its closest relative, with numerous Malay and Javanese loanwords. It is known that Ma'anyan people were brought as laborers and slaves by Malay and Javanese people in their trading fleets, which reached Madagascar by ca. 50–500 AD. These pioneers are known in the Malagasy oral tradition as the Ntaolo, from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *tau-ulu, literally 'first men', from *tau, 'man', and *ulu, 'head; first; origin, beginning. It is likely that those ancient people called themselves *va-waka, "the canoe people" from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *va, 'people', and *waka 'canoe'. Today the term vahoaka means 'people' in Malagasy.

The Southeast Asian origin of the first Malagasy people explains certain features common among the Malagasy, for instance, the epicanthic fold common among all Malagasy whether coastal or highlands, whether pale, dark or copper skinned. This original population (vahoaka ntaolo) can be called the "Proto-Malagasy".

Traders, Explorers, and Immigration

Omani Arabs

The written history of Madagascar begins in the 7th century when Omanis established trading posts along the northwest coast and introduced Islam, the Arabic script (used to transcribe the Malagasy language in a form of writing known as the sorabe alphabet), Arab astrology and other cultural elements. During this early period, Madagascar served as an important transoceanic trading port for the East African coast that gave Africa a trade route to the Silk Road and served simultaneously as a port for incoming ships. There is evidence that Bantu or Swahili sailors or traders may have begun sailing to the western shores of Madagascar as early as around the 6th and 7th century.

Neo-Austronesians

According to oral tradition, new Austronesian clans (Malays, Javanese, Bugis, and Orang Laut), historically referred to in general, regardless of their native island, as the "Hova" (from Old Bugis uwa, "commoner") landed in the north-west and east coast of the island. Adelaar's observations of Old Malay (Sanskritised), Old Javanese (Sanskritised) and Old Bugis borrowings in the initial Proto-Southeast-Barito language indicate that the first Hova waves came probably in the 7th century at the earliest. Marre and Dahl pointed out that the number of Sanskrit words in Malagasy is very limited compared with the large number now found in Indonesian languages, which means that the Indonesian settlers must have come at an early stage of Hindu influence, that is ca. 400 AD.

Bantus

There is archaeological evidence that Bantu peoples, agro-pastoralists from East Africa, may have begun migrating to the island as early as the 6th and 7th century. Other historical and archaeological records suggest that some of the Bantus were descendants of Swahili sailors and merchants who used dhows to traverse the seas to the western shores of Madagascar. Finally some sources theorize that during the Middle Ages, Arab, Persian and Neo-Austronesian slave-traders brought Bantu people to Madagascar transported by Swahili merchants to feed foreign demand for slaves. Years of intermarriages created the Malagasy people, who primarily speak Malagasy, an Austronesian language with Bantu influences. There are consequently many (Proto-)Swahili borrowings in the initial Proto-SEB Malagasy language. This substratum is especially significantly present in the domestic and agricultural vocabulary (e.g. omby or aombe, "beef", from Swahili ng'ombe; tongolo "onion" from Swahili kitunguu; Malagasy nongo "pot" from nunggu in Swahili).

Europeans

Europe knew of Madagascar through Arab sources; thus The Travels of Marco Polo claimed that "the inhabitants are Saracens, or followers of the law of Mohammed", without mentioning other inhabitants. Other than its size and location, everything about the island in the book describes southeastern Africa, not Madagascar. European contact began on 10 August 1500, when the Portuguese sea captain Diogo Dias sighted the island after his ship separated from a fleet going to India. The Portuguese traded with the islanders and named the island São Lourenço (Saint Lawrence). In 1666, François Caron, the director general of the newly formed French East India Company, sailed to Madagascar. The company failed to establish a colony on Madagascar but established ports on the nearby islands of Bourbon (now Réunion) and Isle de France (now Mauritius). In the late 17th century, the French established trading posts along the east coast. On Île Sainte-Marie, a small island off the northeastern coast of Madagascar, Captain Misson and his pirate crew allegedly founded the famous pirate utopia of Libertatia in the late 17th century. From about 1774 to 1824, Madagascar was a favourite haunt for pirates. Many European sailors were shipwrecked on the coasts of the island, among them Robert Drury, whose journal is one of the few written depictions of life in southern Madagascar during the 18th century. Sailors sometimes called Madagascar "Island of the Moon".